Poverty is a real problem affecting millions of people worldwide: what has been done so far to curb it? With what outcomes? Can more be done?

Poverty is defined based on a threshold, aptly called “poverty line”, which the World Bank determines at $3 per day: based on this criterion, about 808 million people in the world live in conditions of true economic hardship, despite the situation having notably improved over time. Many, indeed, are the solutions put in place over the years to address this problem. Have efforts been enough? Can more be done?

Poverty: definition

Poverty, according to the World Bank, is the “marked deprivation of well-being”. In this sense, those who do not possess the necessary income to purchase a “minimum basket” of socially accepted consumer goods are considered poor. In other words, those living in poverty do not possess sufficient monetary resources to meet a minimum threshold deemed adequate, called the poverty line.

A broader definition of poverty – and therefore well-being – focuses on one criterion in particular: the individual’s ability to live and, in general, “function well” within society. In this way, poverty is also calculated based on access to education, healthcare, freedom of expression and so on.

Returning to the concept of the poverty line, the World Bank quantifies this limit in two ways: relative and absolute. While the former considers each case, identifying a figure in dollars based on a country’s characteristics, the latter determines a universal value.

The poverty line varies periodically as macroeconomic conditions vary. In 1990, at its introduction, the absolute threshold was set at $1 per day for low-income countries, while in June 2025, with the latest update, it was raised to $3 per day.

What are the causes of poverty?

Poverty – to say something not trivial and little rhetorical – is a complex concept, the fruit of the interaction of multiple causes. In any case, the EAPN (European Anti-Poverty Network) identifies some key factors: low levels of education, high unemployment, and a strong presence of underpaid jobs, as well as the absence of a Welfare State that can help those in difficulty, to cite a few.

These are, evidently, elements that are simultaneously cause and consequence. Simplifying to the extreme: a poor State, to “stay standing” and not fail, will probably be forced to cut social spending and investments, creating the conditions for low schooling and high unemployment, which, in turn, will prevent citizens from educating themselves and accessing jobs with higher wages. Internal consumption collapses, the economy does not grow, and the State impoverishes further and cuts social spending… etcetera, etcetera.

There exists, however, an indicator that, more than others, positively correlates with a Country’s poverty: when one rises, the other rises and vice versa. We are speaking of foreign debt, i.e., the part of debt held by non-resident creditors in the given country, including both public and private foreign debt.

The former is composed of bonds and government securities – thus financial instruments issued by the state – held by foreign investors; the latter, instead, is the debt that private subjects, such as companies and banks, accumulate towards external subjects.

Why does foreign debt have such an important role?

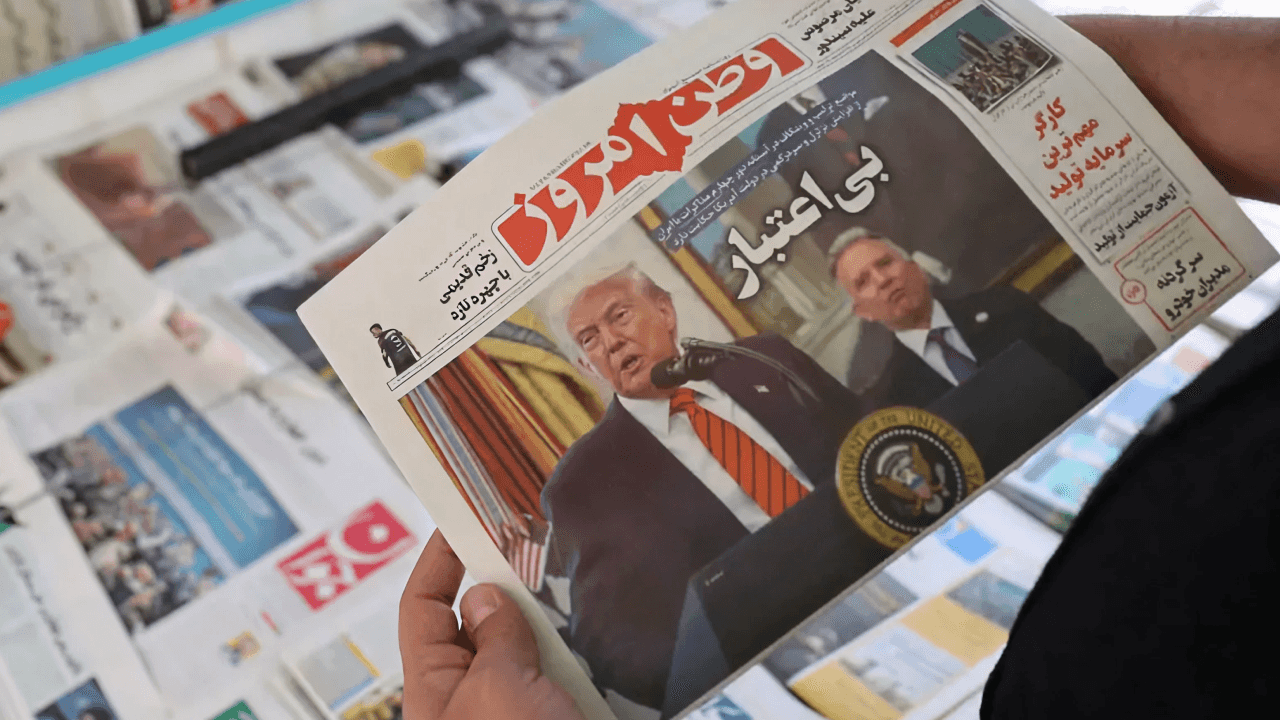

Poverty, as we have just written, is correlated with foreign debt: they are both high where the other is high. The reason, fundamentally, is encapsulated in two words: the original sin, i.e., the impossibility for a LIC (Low Income Country) to issue debt to foreign investors in its national currency, with all the repercussions we will tackle shortly.

The term, borrowed from Christianity, plays precisely on the religious analogy: just as the human being is born inheriting Adam’s condition of sin, in the same way LIC Countries are born already guilty,” inheriting structural difficulties that do not depend on the policies implemented, but on the global financial system that does not trust their currency.

The original sin, currency mismatch and its consequences

This is the crux of the matter: while high-income Countries, like the United Kingdom, can distribute a large part of their debt in their national currency, i.e., the pound, LIC Countries are forced to resort to strong foreign currencies, such as the dollar, the euro, or the yen. This produces the so-called currency mismatch, namely the difference between the currency in which a Country issues debt and that in which it generates income, with all the negative effects that ensue.

Imagine wanting to finance Madagascar’s debt with $1,000, a LIC Country with high foreign debt, by purchasing a 3-year Government bond. The Malagasy Treasury, at this point, proposes two solutions: you can buy the bonds directly in dollars, knowing that the repayment with interest will occur in dollars, or you can convert the 1000 dollars into 4,487,736 ariary (the local currency), with relative repayment, in three years, i n ariary. The problem is that Madagascar has very high inflation. It is clear, therefore, that you will choose the first option.

Madagascartherefore has very few opportunities to issue debt inAriary because, realistically, any investor, like you, will prefer the dollar. Here is the currency mismatch: foreign debt and interest rates are in dollars, whilst state revenues are in local currency; if the exchange rate with the dollar remains stable, the problem does not arise. Unfortunately, this is not the case for Madagascar: in 2017, the dollar-to-ariary exchange rate was 1 to 3,000; today, it is 1 to 4,488.

Currency mismatch is deleterious because it sharply amplifies shocks. Let’s imagine a scenario where Madagascar is hit by an endogenous crisis, like a coup d’état, or an exogenous one, like a natural catastrophe: capital flight from the Country is practically guaranteed, since any investor would try to preserve their assets by taking refuge in more solid assets. The result? The currency, already very weak, would devalue even more, with a consequent drastic increase in the cost of debt service – the total amount the State must pay to investors. The consequence? Liquidity crisis and probable default.

The compression of social spending

Shocks aside, original sin notably limits the State’s spending margin in a Country like Madagascar due to a paradox that Marco Zupi, a geopolitical analyst and author of an article on the theme of debt sustainability, calls “double truth”. Despite public debt often being greater in advanced economies, LDCs must reckon with a disproportionately higher relative debt burden.

In simple terms, even if Madagascar holds public debt significantly lower than Italy’s, it still pays a much higher relative cost and must use a disproportionate share of its scarce revenues just to pay the interest. These, indeed, are high both because investors, given the risk, require adequate premiums, and because, as we have seen, the African state’s inflation notably devalues the Malagasy ariary. All this leads to the compression of social spending, namely the cutting of funding for education, public works, healthcare and so on.

Staying on the theme, the indebtedness of African states, as Zupi writes, reached its highest level in the last decade in 2023, with a debt-to-GDP ratio equal to 61.9%. In general, in 2024, developing countries spent, on average, 15% of public revenues on foreign debt payments, up 6.6% from 2010. All this, as we explained a little above, reduces the possibility for a LIC Country to invest in welfare, to the detriment of its citizens: for example, in at least 34 African Countries, spending on foreign debt payment is higher than that for education and healthcare – in the three years 2021-2023, this was respectively 70, 63 and 44 dollars per capita. Even at a global level, almost 3.4 billion people live today in Countries forced to direct public spending in this way.

Initiatives for debt reduction in LIC Countries

The international community, beginning in the mid-1980s, sought to curb this phenomenon, evidently with scant success. Specifically, six initiatives have been put in place to reduce the LIC Countries’ dependence on debt and enable them to achieve more organic, healthy development. Let’s quickly look at the projects and why they didn’t work.

Baker Plan (1985-1988)

With the Baker Plan, in two words, liquidity was privileged, flooding Countries in difficulty with new loaned capital. The strategy was moved by the conviction that these States were merely illiquid, i.e., temporarily without sufficient money to repay the debt.

In reality, the diagnosis was wrong: more than illiquidity, it would have been appropriate to speak of structural insolvency, namely the impossibility of repaying a debt, because it is too high, even in the long run.

The Baker Plan, therefore, “provided oxygen” and avoided systemic crises in the short term, without, however, tackling the underlying criticality. In summary, it postponed the problem without solving it.

Brady Plan (1989 onwards)

The consequence of the failure of the Baker Plan: the international community recognised that the main obstacle was not a lack of liquidity but the extent of the debt and the relative structural insolvency. There was another problem to solve: the bank loans of the Baker Plan, by now, had become uncollectible, i.e., junk, since no state would ever honour the debt. What to do?

Bank loans are converted into securities guaranteed by strong collateral – like US Treasury Bonds, one of the safest investments in the world – called, precisely, Brady Bonds. But on one condition. Simplifying, the Brady Plan says to banks: Your 10 billion loan is worth nothing, but now you can swap it for a 7 billion Brady Bond”. Naturally, banks accept, because losing 30% of the investment is better than losing 100%, and the debt is discounted – no longer 10 but 7 billion to be repaid.

The goal was to reopen market access for LIC Countries via guaranteed Brady Bonds, which reduced debt and, obviously, made them much more appealing in the eyes of investors than the old junk loans.

However, the entity of reductions was limited and insufficient to make the debt sustainable: to resume our invented example, the discount from 10 to 7 billion was useless for a State that could not repay even 5.

Heavily Indebted Poor Countries and Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (1996 – 2005)

These two initiatives, which we will call respectively HIPC and MDRI, were born in response to the failure of the previous plan and, according to experts, represent the most ambitious attempt ever to reduce LIC Countries’ foreign debt.

So, after learning the lesson of the Baker and Brady Plans, the international community intervened directly on the debt: with HIPC, cuts up to 90% of liabilities occurred, whilst with MDRI, one arrived at cancelling 100% of LIC Countries’ debt towards international institutions like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Finally, fiscal space was effectively freed, and low-income Countries could use surplus capital, which had been shortly before destined for the payment of interest and bonds, for social spending: “in Tanzania and Uganda”, as Marco Zupi writes, “spending on education and healthcare increased significantly after debt cancellation”.

What didn’t work? To summarise, HIPC and MDRI solved part of the past problems since, according to the World Bank, a good 37 Countries would have benefited from more than 100 billion dollars of “discount”. These initiatives, however, failed to prevent future crises. Aside from the imposition of quite rigid conditions for financing, no targeted intervention for system reform was realised or even considered, leaving intact the structural difficulties at the root of the “original sin” of LIC Countries and all that ensues. These Countries, by mathematical certainty, started accumulating debt upon debt again.

But that’s not all! We are in the third millennium, the world is changing, and new protagonists are emerging. This is to say that, if “old debts” were contracted mainly towards Member States of the Paris Club – including the USA, UK, Italy, Germany, Japan and Canada – and multilateral banks like the World Bank, now we have a string of new creditors: from non-Paris Club States like China, to private creditors like investment funds and commercial banks.

In summary, the new order of creditors has contributed – and still contributes – to making various crises much more complex: if before there existed a single table – the Paris Club – that organised and carried forward negotiations, now the scenario is much more fragmented and difficult to coordinate.

Debt Service Suspension Initiative (2020-2021)

The DSSI was an initiative launched by the G20 – the 20 major economies of the world – during the COVID-19 pandemic. As is easily intuitable from the name, the DSSI is intended to temporarily pause debt payments: it was a suspension of about 13 billion dollars in payments for 48 Countries, thereby increasing their availability to combat the health crisis.

The DSSI, at the level of underlying logic, is very similar to the Baker Plan, since both programmes focused on liquidity rather than solvency, with concentrated interventions on temporary relief rather than structural deficits. The only real difference lies in the modalities through which the objective was reached: with the Baker Plan, bank loans were granted, whilst with DSSI, the interruption of payments was simply allowed.

As for logic, the two initiatives also share limits: in the design of DSSI, no long-term strategy was planned, but the emergency context in which it takes hold must be considered. In this case, however, a side effect occurred that the author of the article on debt sustainability (Marco Zupi) defined as “perverse”.

The stop on payments, in fact, concerned only “official creditors”, namely Member States of the Paris Club, without touching private creditors: banks and investment funds continued to receive due consideration.

Common Framework (2020 – present)

It is the current initiative put in place by the G20. It has many points in common with HIPC and MDRI: the Common Framework (CF) was also designed to tackle the issue at the root, intervening in countries’ solvency and thus reducing the total debt stock to a sustainable level.

Given that it is in progress, it is difficult to judge its effectiveness. The main criticisms, however, refer to the slowness of the programme’s procedures. In two words, citing the author, “discounts, when they arrive, do so late and often after costly periods of uncertainty”. Furthermore, there is a knot to untie regarding the involvement of private individuals who, due to the unattractiveness of the incentives, decide not to participate.

How will the situation evolve?

It is clearly a rhetorical question to which no one can give a definite answer: even the initiatives described so far, which were indeed motivated by an (apparent?) underlying solidarity, have partly failed in their intent, testifying to the structural complexity that distinguishes the financial system.

Meanwhile, it is possible to reason on some solutions that, in the immediate future, could offer a sort of financial self-defence tool to victims of this system. Let’s return to the case of Madagascar: its inhabitants have seen the ariary, the local currency, devalue by 50% since 2017. How to put the brake on inflation?

Poverty and the role of cryptocurrencies

Let’s start with a premise: according to the Global Findex 2025 published by the World Bank, almost 1.5 billion people worldwide are unbanked, i.e., do not have a current account. At the same time, still according to the same report, 86% of adults possess a mobile phone – the percentage drops to 84% in LIC Countries. Finally, crossing data, 42% of unbanked adults possess a smartphone.

The fundamental point is that there exists a vast part of the world population without financial access that, however, already possesses the basic infrastructure, namely phone and internet connection, to be able to solve the problem, said, paraphrasing a proverb, “they have teeth but no bread”.

A smartphone connected to the internet, for example, is enough to be able to install a wallet and buy, sell, send and receive cryptocurrencies – and finally use teeth to eat bread. But why could cryptocurrencies represent a brake for inflation? Let’s continue with the example of our beloved Madagascar.

Case 1: King Julien XIII buys crypto

We therefore have an unbanked inhabitant of Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar, who possesses only a smartphone on which he has installed a crypto wallet. Our inhabitant, whom we shall call King Julien, in honour of the film Madagascar, wants to convert his ariary into Bitcoin or stablecoins, such as USDC, because he is fed up with seeing his capital diminish day after day due to inflation. First of all, King Julien must overcome the biggest obstacle: being unbanked, he must find a way to digitise his cash.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where many face the same impediment as King Julien, a very widespread solution exists: Mobile Money, a financial service that allows one to receive, send, and store money via a smartphone SIM.

King Julien XIII, therefore, goes to one of the many telephony shops around Antananarivo, hands over his cash ariary, and receives the equivalent amount, minus a commission, on his Mobile Money account. Let’s remember that King Julien, despite having digital money, is still unbanked, i.e., lacking a current account at a bank. For this reason, he cannot use an exchange.

King Julien chooses another approach and uses a peer-to-peer (P2P) platform to find a seller who accepts his payment method. Once found, the transaction takes place: as soon as the seller confirms receiving payment, they unlock the Bitcoin or USDC – previously held in escrow as a guarantee deposit – which the platform then transfers to the buyer’s crypto wallet.

King Julien is now sure that his capital will not devalue as happened previously with the ariary. To spend the money, thus converting Bitcoin or USDC into ariary, it will suffice for him to carry out the reverse process.

Case 2: King Julien receives crypto from abroad

To conclude, let’s see another case: King Julien receives crypto from a relative who emigrated to Italy, where, as of January 1, 2024, the resident Malagasy population is 1,675 units. As we have seen, King Julien is unbanked and cannot receive a bank transfer. But here too, crypto comes to our aid with a quicker procedure than in Case 1.

The relative, via Young Platform, converts their euros into Bitcoin or USDC in a second and sends them to King Julien’s wallet, who can then convert them back into ariary through the reverse process we mentioned a little while ago. This time, too, King Julien managed to save his capital from inflation.

The problem is not solved, but King Julien lives better

To conclude, a brief reflection: it is clear that, in this way, the knot of poverty is not untied, and it remains a priority issue on the international agenda. However, a solution like the one just exposed can help inhabitants of LIC Countries a lot. At least those with a phone.