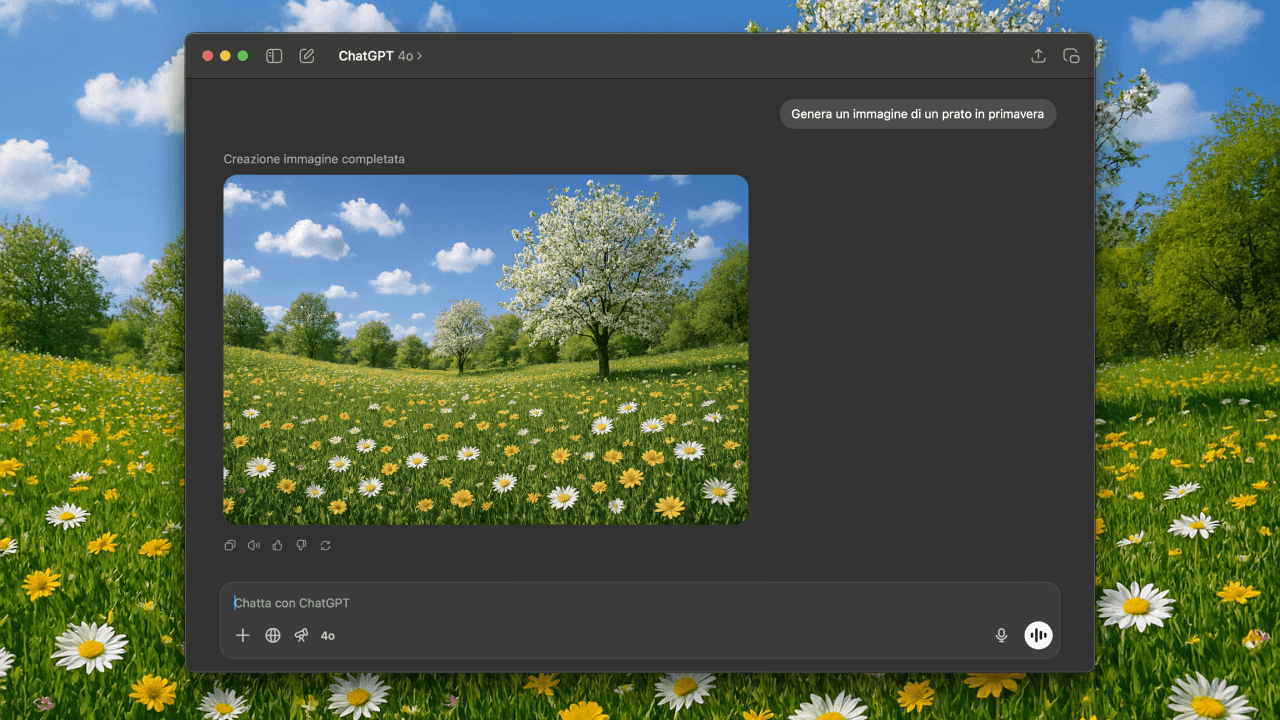

How to create images using artificial intelligence: Where do we stand? Discover all the steps in this comprehensive guide.

If you, too, have seen the images created by artificial intelligence – and if you haven’t, who knows where you live – your crevello will have ventured an argument like this. There was a time, not so long ago, when creating an image required pencils, brushes, cameras or, for the more modern, graphics tablets and hours of painstaking patience. Then, almost out of nowhere, generative artificial intelligence exploded. Suddenly, our social feeds, company presentations and even group chats were filled with dreamy, hyper-realistic and bizarre images, all spawned by an algorithm. “You want a Van Gogh-style astronaut cat eating ice cream on Mars? Give me two minutes.”

This new frontier of digital creativity has triggered a mixture of wonder and apprehension. On the one hand, the promise of democratising art, of giving anyone the power to visualise the impossible; on the other, the fear of a future where real artists, those in the flesh, end up begging robots. But before we panic or exclaim, let us try to understand how artificial intelligence creates images.

Creating images with artificial intelligence: what’s behind the magic?

Behind the apparent wizardry of an image that comes from a simple sentence, there is a concentration of technology that, until a few years ago, was the stuff of science fiction films. We are talking about machine learning and neural networks, i.e. software that attempts to imitate the functioning of the human brain. These systems are ‘trained’ on endless databases containing billions of existing images, each accompanied by a textual description.

The models most in vogue today, such as those based on ‘Diffusion’ architectures (such as Stable Diffusion, DALL-E 3, Midjourney), learn to associate words with visual concepts. In practice, they start from a digital ‘noise’, a kind of indistinct fog, and, guided by our textual input (the famous ‘prompt’), begin to ‘sculpt’ this noise, one small step at a time, until the required image emerges. Imagine a sculptor pulling a statue out of a shapeless block of marble, only the marble is digital, and the chisel is an algorithm that has seen more works of art than any living critic. The result? Sometimes a masterpiece, other times something that looks like something out of a Dali nightmare after a heavy dinner.

How to generate images with AI: instructions for use

If you think it is enough to type ‘cat’ to make artificial intelligence create the image of a purring feline from the screen, you will be disappointed. The art of dialoguing with these AIs, known by the somewhat pretentious Anglophone term prompt engineering, is a subtle discipline, somewhere between poetry and programming.

You have to be specific, almost pedantic. You want a ‘dog’? Fine, but what breed? What is it doing? Where is it? In what light? In what pictorial style? “A golden retriever puppy sleeping blissfully in a red velvet armchair, illuminated by warm afternoon light, Renaissance oil painting style”. There, now we’re getting somewhere.

Then there are the negative prompts, or instructions on what NOT to do: “no double tails, please”, “avoid that plastic effect”, “I beg you, no more than five fingers on each hand!”. The process is iterative: you generate, observe the result, refine the prompt, regenerate, and so on, in a loop that can lead to the perfect image or to deciding that, perhaps, a hand-drawn picture was better. At first, it is easy to get digital abominations: that ‘cat on a bike’ might turn into a Lovecraftian tangle of fur and pedal metal. But with a little practice (and a lot of patience), you can begin to tame the algorithmic beast and start creating quality artificial intelligence (AI) images.

Lights and shadows: the pros and cons of AI-generated images

Like any self-respecting technology, image-generative AI also brings with it a wealth of opportunities and a few skeletons in the cupboard. Here is a brief summary of what, at least in our opinion, are the pros and cons of this technological breakthrough.

Pros:

- Democratisation of creativity: anyone, even someone who draws like a three-year-old, can give visual form to their ideas. Need a logo on the fly? An illustration for a post? An inspiration for a tattoo? Ask and (maybe) you’ll get it;

- Speed and efficiency: for designers, creatives and marketers, it is a crazy tool for brainstorming, creating moodboards, concept art, and rapid prototypes. Hours of work condensed into a few minutes;

- New aesthetic horizons: AI can mix styles, invent perspectives, create images that a human might not conceive, opening up unprecedented art forms;

- Pure fun: let’s face it, asking the AI to draw absurd things is often hilarious;

Cons:

- The six-finger nightmare (and other amenities): the infamous ‘uncanny valley’ is always lurking. Hands with too many or too few fingers, faces that melt like wax, seasick perspectives, objects that defy the laws of physics. Sometimes, the results are so surreal that they themselves become an unintentional art form.

- The fair of the generic: with the ease of use, the risk is a rising tide of images that are aesthetically pleasing but devoid of soul, all a bit the same, a bit ‘Midjourney effect’. The world is now invaded by cyberpunk kittens with a variable (but hardly ever correct) number of legs.

- The crisis of originality: if everyone uses the same tools and maybe even similar prompts, don’t we risk a stylistic flattening?

- But is this art?: the debate is open and heated. If a machine ‘makes’ the work, is it still art? Who is the artist? Who writes the prompt, or the algorithm? My cousin, who until yesterday was only making memes of dubious quality, now calls himself ‘an international prompt artist’, complete with a portfolio on LinkedIn.

And from a philosophical point of view?

And here the matter gets serious, because the implications go far beyond the number of fingers. The first problem, which has long been central to the debate on artificial intelligence, not only when it is used to create images, is related to copyright and the question: whose image is generated? Of the user who wrote the prompt? Of the company that created the AI? Or is it a derivative of the myriad images used for training, many of which may be copyrighted? At the moment, it’s a legal Wild West. And what about the prompting ‘in the style of [famous living artist]’? Is it homage or theft?

Then there is the work-related issue. Will artificial intelligence destroy the market for illustrators, photographers, graphic designers, or just make it more productive? We like to be optimistic, imagining a world where AI is a powerful ‘creative assistant’, freeing humans from superficial tasks and allowing us to focus on the most valuable tasks.

Let us close with the two main ethical dilemmas. The first is frightening and concerns the ease with which false but realistic images can be created with intelligence. Photos of events that never happened, faces of people stuck on the bodies of others. The implications in terms of disinformation, manipulation of public opinion, and trust in sources are enormous. Distinguishing the true from the plausible will become an increasingly challenging task.

Finally, it must be emphasised that AIs are trained on data created by human beings. If this data contains prejudices (gender, ethnic, cultural), the AI will learn and replicate them, which may lead to the creation of stereotypical images or the exclusion of certain representations. The algorithm, in short, can be as racist or sexist as the societies that nurtured it.

In short, the possibility of creating images with artificial intelligence is certainly as revolutionary as the invention of photography or digital photo editing. As we are increasingly realising, AI is an incredibly powerful tool, capable of democratising creativity, accelerating production processes, but also raising profound questions about the nature of art, work and truth itself. Like any tool, its impact – beneficial or maleficent – will depend on how we choose to use it, adjust it and integrate it into our lives. It is neither a demon to be exorcised nor a magic wand that will solve every problem. It is, more prosaically, a powerful new set of digital crayons available to humanity. Get ready for a future where, in order to understand whether your friend’s holiday photo is real or ‘prompt’, you will need a trained eye, a second coffee and, perhaps, an honorary degree in the philosophy of perception. The good (and the bad) has just begun.