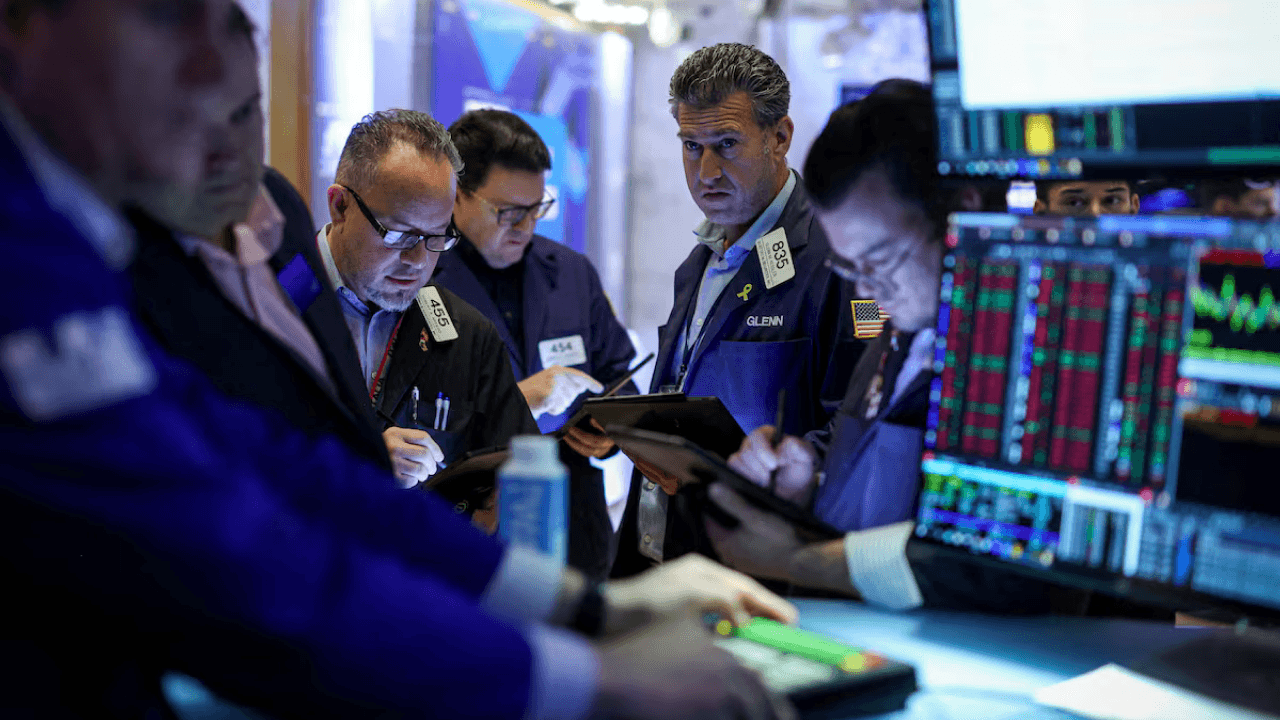

NYSE, Nasdaq, LSE – what do these names mean? They refer to some of the world’s leading stock exchanges. But what exactly is a stock exchange, and how does it work?

The stock exchange, more commonly known as the stock market, is a financial marketplace where shares, bonds, and other securities are bought and sold. Once considered the domain of financial insiders, the stock market has now entered popular culture, thanks in part to numerous cult films that have graced cinema screens since the 1970s.

But what is the history of the stock exchange? What are its key components? And who are the leading players involved? Let’s take a closer look.

How and when was the stock exchange created?

The earliest recorded evidence of trading, lending, and deposit activities dates back to the second millennium BC, inscribed in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi. Similar financial practices were also found among the ancient Greeks, Etruscans, and Romans.

However, these early forms of financial exchange cannot truly be considered a ‘stock market’ as we understand it today. The first genuine stock exchange was established in Amsterdam, in the Netherlands, around the 17th century.

The Middle Ages

In the late Middle Ages, the world of finance began to take on a more structured form with the emergence of the first banking institutions. Italy – particularly the cities of Genoa, Venice, and Siena – was, for many years, the central financial hub of Europe.

Around the 14th century, a new trading centre emerged that attracted merchants from across the continent, helping to shape a financial system that was still quite rudimentary. This was in Bruges, Belgium, specifically in the Ter Buerse Palace, built by the aristocratic Van der Bourse family. It was here, where merchants gathered to exchange goods and currencies, that the name ‘Borsa’ (stock exchange) originated.

Later, essential exchanges were established in Antwerp, Lyon, and Frankfurt, marking a shift from private to public management, with increasingly clear and stricter regulations.

The Modern Age

In the 17th century, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange became the most important in Europe – and likely in the world. This period also saw the creation of the first joint-stock companies, which significantly boosted the trading of securities, including government bonds and commodities.

The 18th century witnessed the rise of international trade, as well as the emergence of speculative bubbles. The most famous was the South Sea Bubble in England (1710–1720), when share prices soared before collapsing, causing heavy losses. It led to the Bubble Act, a law aimed at curbing speculation by limiting the formation of new companies.

Meanwhile, in New York, a group of merchants began meeting under a plane tree on Wall Street to trade securities – a humble beginning for what would become a future global financial centre.

The Industrial Revolution and the modern stock market

During this period, the stock market became crucial not only for company growth but also for the economic development of entire nations. London and Paris became key financial markets, funding industrial projects, infrastructure, and even colonial and military ventures.

In 1817, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) was officially established. Over time, it would grow to become the world’s largest stock exchange by market capitalisation.

The 20th century: successes and severe financial crises

By 1900, the stock market had become the beating heart of the capitalist system. Economics and finance were now deeply interconnected. It was a century marked by sharp contrasts, alternating between periods of remarkable economic growth – such as the Roaring Twenties and the post-World War II boom – and severe financial crises, including the Great Depression of 1929 and Black Monday in 1987.

This volatility highlighted the need for regulation. Supervisory authorities such as the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) in the United States and Consob (National Commission for Companies and the Stock Exchange) in Italy were established to oversee financial markets, which were now dealing with enormous capital flows.

In 1971, the Nasdaq was founded, marking the beginning of the stock market’s transition from a physical trading floor, filled with shouting and hand signals, to an electronic system driven by computers and algorithms.

The digital age

Fast forward to today: the rise of the Internet has transformed how the stock market functions. It has brought greater accessibility, instantaneous transactions, unprecedented capital mobility, and the emergence of entirely new markets.

Now that we’ve explored its history, let’s take a closer look at how the stock market works today.

How does the stock market work?

To understand how the stock market works, it’s first essential to understand what it is. The stock market can be described as the financial engine that links the world of businesses with that of savers and investors. On one side, companies seek capital to fund their growth – whether by opening new branches, developing new products, or hiring staff. On the other hand, individuals look for opportunities to grow their savings. This is where the concepts of primary and secondary markets come into play.

The primary market is where shares are created. When a company lists on the stock exchange for the first time, it sells its shares directly to investors – a process known as an IPO (Initial Public Offering). Investors, by purchasing these shares, provide the company with the necessary funds to grow.

The secondary market, on the other hand, is the market in which existing shares are bought and sold between investors on a daily basis. Companies do not earn money from these transactions, but the market allows investors to profit from rising prices.

But shares are not the only financial instruments traded on the market. A large portion of investments also involves bonds. Understanding the difference between the two is fundamental.

What are shares?

As mentioned earlier, shares represent small units of ownership in a company. Investors buy them with the hope of selling them later at a higher price. Even by purchasing a single share, an investor becomes a partial owner of the company.

This ownership grants specific rights, such as receiving dividends (a portion of the company’s profits, although not always guaranteed) and participating in shareholder meetings.

However, buying shares comes with risks. Share prices are closely tied to the company’s performance. If the business thrives, the price typically increases. If it struggles, the cost can fall – sometimes dramatically. In extreme cases, shares can become worthless.

This is because share prices are determined by the balance of supply and demand. The more people want to buy a share – perhaps because the company has released a revolutionary product or reported record profits – the more its price rises. If demand drops, the price falls.

A helpful analogy: how much would you pay for a bottle of water in a city? Probably not much – it’s easy to find. But how much would you pay for that same bottle in the middle of the desert?

What are bonds?

Bonds differ fundamentally from shares. When an investor buys a bond, they do not become a shareholder; instead, they become a creditor. What does that mean in practice?

Put simply, a company issues bonds to raise capital, just as it does when issuing shares, but the mechanism is different. Buying a bond is similar to lending money to the company. The investor agrees to lend a specific amount, understanding that it will be repaid after a set period (e.g., five or ten years). In return, the company pays the investor regular interest payments, commonly referred to as coupons.

These coupons function like an interest rate, and the amount paid often reflects the company’s financial stability and trustworthiness. A well-established, transparent, and profitable company will typically offer a lower interest rate than a riskier, less stable one.

The same principle applies to government bonds, which a national government issues to finance public spending. For example, Italian government bonds tend to offer lower interest rates than Moldovan bonds, because Italy is generally considered more creditworthy and therefore less risky for investors.

Compared to shares, bonds are considered safer and more stable. However, this usually means they offer lower potential returns. As always, the general rule applies: higher risk, higher reward – lower risk, lower return.

What are indices?

This bonus section ties together both shares and bonds. So, what exactly is an index?

An index is simply a group or “basket” of listed companies (in the case of shares) or debt instruments (in the case of bonds), grouped according to specific criteria.

What kind of criteria? For example:

- The S&P 500 includes the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the United States.

- The NASDAQ-100 tracks the 100 largest non-financial companies listed on the NASDAQ.

- The S&P Global Clean Energy Transition Index includes 100 companies worldwide that are involved in the clean energy sector.

For bonds, indices might group securities by maturity date, such as all government bonds with a 10-year or 30-year term.

These indices are useful benchmarks. They help investors assess overall market performance, track sectors, and compare their portfolios against broader trends.

Who operates on the market? The main players

Now that we’ve explored the tools and rules of the stock market, it’s time to understand who actually takes part.

Listed Companies

First of all, there are the listed companies themselves – without them, the stock market wouldn’t exist. As we’ve seen, these companies launch themselves into the financial markets to raise capital for expansion, innovation, or operations.

Investors: institutional and retail

Next, we have the investors, who buy shares and bonds in the hope of growing their capital. Investors can be categorised into two main groups: institutional investors and retail investors.

- Institutional investors are the heavyweights of the financial system. They manage enormous sums of money and can influence the price trends of individual companies. This group includes mutual funds, pension funds, and insurance companies, which invest their clients’ money to generate returns and earn management fees in the process.

- Retail investors, on the other hand, are individual savers who invest their own capital in the hope of earning a return on investment. If you’re reading this, chances are you already are – or soon will be – a retail investor. If so, we recommend checking out our blog for helpful content on avoiding common mistakes, understanding diversification, and overcoming cognitive biases in finance.

Financial intermediaries

Let’s now turn to the players who make investing possible: the financial intermediaries.

These operators form the essential bridge between those who issue shares and bonds and those who buy them. For various technical, legal, and security reasons, it’s not possible to trade directly on the stock exchange without going through these entities. In practical terms, we’re talking about banks and online brokers, which provide access to financial markets in exchange for commissions.

You might wonder, perhaps with mild irritation, “Why am I forced to go through an intermediary just to buy a share in Coca-Cola?” The answer is simple: for the same reason you need a driving licence to operate a car. You can’t just jump behind the wheel and press the pedals at random.

You might rightly argue that once you’ve got your licence, you can drive yourself. True – but can you build the car?

That’s the point. Building the “car” in this case means having ultra-secure IT systems, legal authorisations, direct exchange connections, and regulatory compliance. It’s a complex, expensive, and highly regulated activity – which is why supervisory authorities require only authorised intermediaries to operate in this space.

Supervisory authorities

Speaking of oversight, let’s talk about the supervisory authorities – the referees of the financial world. If the stock market were a football match, these are the officials ensuring that the game is played fairly and in accordance with the rules.

These authorities may be national, such as the SEC in the United States, CONSOB in Italy, or the FCA in the UK, or supranational, like ESMA (European Securities and Markets Authority) in the EU.

Their key responsibilities include:

- Investor protection – ensuring that intermediaries act reasonably and responsibly towards consumers;

- Market transparency – requiring listed companies to publish relevant information such as financial reports, quarterly results, and even executive changes;

- Fair trading – monitoring markets to detect and sanction unfair practices like insider trading, where individuals trade using confidential or privileged information.

But you never stop learning.

In this article, we aim to provide an overview of the stock market, outlining its key components and how it operates. That said, what you’ve just read is likely just the tip of the iceberg.

Suppose you’ve landed here fresh from watching The Wolf of Wall Street, dreaming of sipping Martinis on a sun lounger in a luxury resort in the middle of the Pacific within a year, just like the next self-proclaimed guru. In that case, our advice is this: stay grounded and start learning seriously.

In the meantime, why not subscribe to our Telegram channel or even sign up directly to the Young Platform by clicking below? We regularly share guides, tips, and financial updates to help you stay informed and avoid being caught off guard.

See you next time!